My large work table takes up far too much space in my little workroom. I've been meaning to get it downstairs for a while, but wanted to get a few quilts basted up for hand quilting before I did so. So I've been going through my unfortunately large pile of pieced tops to see what I wanted to work on, and came across the one above that Lyra is admiring. In an incongruous way, it reminded me of attending the post-sabbatical show of a Winnipeg painter nearly forty years ago. His enormous canvases were mostly painted in dark greyed-out colours with floating abstract and jagged shapes articulated in charcoal. A naive graduate student at the time, I asked what I was supposed to see, and he explained his work to me patiently and carefully. What I was supposed to see was quite interesting, but I couldn't quite see it. For me, that incident has always stood for the gap between conception and finished work of art. Theodore Adorno talks about that magical moment when the work of art is the equivalent of itself. Since I read his Aesthetics in English, I feel I can't be exactly sure what he means, but I suspect most artists have felt it occasionally: your poem or painting or photograph actually comes close to what you wanted to achieve. Conversely, we all know art, sometimes our own, sometimes others', that fails that test. We know and can articulate what we want to do but can't quite pull it off. I should say that moments ago I found his paintings online and was quite moved. That adds another variable that frustrates many of us: some people can see a work that is the equivalent of itself. Some can't.

As a quilter, I try to evoke a mood. As well, I want to make something visually engaging, something that makes you want to look at it carefully and begin to see the juxtapositions of fabrics I've made. Perhaps it even prompts you to look at the way my tiny little points--sometimes eight at a time--meet up exactly. Craftsmanship is often as important as conception. But when I looked at that little quilt, well crafted though it was, my reaction was "Meh."

I haven't been sleeping well lately, so a couple of days after I looked at those nice block in their unexciting setting, I spent my insomniac hours taking it apart, rescuing the blocks. As I did so, I found myself considering the challenges I'm facing as a writer. It isn't enough that the work is well-crafted. At the ground floor of literature lies the challenge of word choice and sentence structure, rhythm and sound. I'm good at that. In my teens, I was a champion at sentence diagramming, and given a single sentence, I can still probably come up with three or four other syntaxes. Then out comes the old thesaurus--I handle it gingerly because it is falling apart--where I consider word choice and the kinds of sound and rhythm that might undergird the sense. In other words, my hands told me as I wielded my seam ripper, I can make good blocks. But do I have a vision? And here is the question I think many writers are asking themselves today: do I have a vision that other people will care about or consider significant?

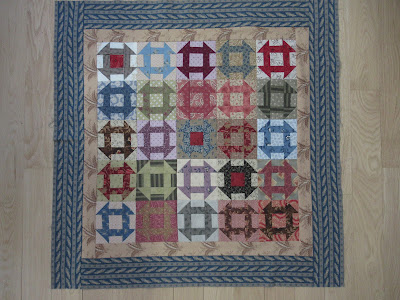

The quilt above is put together in one of the traditional ways quilters use: pieced blocks alternate with plain blocks. Sometimes, as in the quilt on the right that I made for Nikka some years back, the plain blocks contain lots of quilting. There are some advantages to this structure. First, you don't have to make so many pieced blocks, which takes quite a lot of time. In the finished version below, which is thirty inches square, there are 433 pieces. They all had to be sewn together. Plain blocks can also calm a quilt down. But I could see that no amount of quilting was going to make those 4 1/2 inch blocks interesting, while blocks pieced together can yield secondary patterns. In the original version, I'd added a playful touch: I used a toile for the plain blocks, in the order in which I cut them, so a viewer could actually put the toile back together mentally. Clever, eh? But cleverness is pointless if the quilt is boring or doesn't make a statement. Convention plus cleverness only gets you so far as an artist.

Taking the quilt apart also made me think about revision. When I taught students to write, I would urge them not to revise until they had a whole, partly because they could spend an hour revising a paragraph they might later cut. That advice is meant to save them time, which is at a premium when you are taking five classes and each of your professors wants a research paper at the end of term. I now don't follow my own advice, instead revising in two ways. I start each day revising what I wrote the day before; that gets me into the flow of what I'm creating. Then I go back to drafting but can make more intimate and subtle connections with what has gone before. And then, of course, there's the big structural revision where you cut what isn't working and reshape what remains. That's the point when I bring my big worktable up from the basement and spread chapters and pages and poems out to see how the whole thing can best be built. That's the point I'd gotten to with the original quilt. To make it the equivalent of itself, I had to be willing to take the whole thing apart.

In the same way, I took four of the blocks from the original quilt and sewed them together to see if they worked or were too busy. Instead, I found they created some echoing patterns; you could see the architecture of the block. Then I sat down to choose fabrics for new blocks--twelve more--cut out more tiny pieces and began putting them together. I had hoped to keep the original borders, so added more blue. It also needed a dash of black here and there for sharpness. I bootlegged the toile I'd used for the plain blocks into one of these. It's turned out to be a cheerful quilt, a bit funky, even though all the blocks are made of reproductions--fabric designed to look like it was made in the nineteenth century. I might even say that the original version is polite; this one isn't.

Here's the part of revising that no quilting metaphor will help with. How do you reveal what's important without getting out your hammer and tacking up a sign? How do you hold your readers, making them what Virginia Woolf called her "co-creators"? How do you find those moments in a draft that are easy and clever but need you to stop and stare at them for half an hour, finding ways to dig more deeply, to push your understanding of the human condition and this magical planet we all inhabit? I think I get there after a while--after a long time. More insomniac nights than it took to take this little quilt apart.

It's clearly Lyra's quilt. When I put it on the floor to photograph, he ran right over and begin posturing.

No comments:

Post a Comment